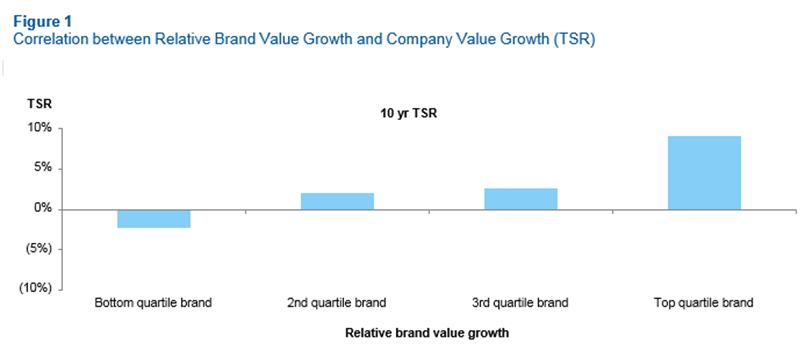

Brands represent a substantial component of a company’s intrinsic value. They almost always form a key pillar around which companies are built and thrive over time. There is a significant correlation between brand value growth and company value growth1, as measured by total shareholder returns (TSR) (Figure 1). However, our recent research suggests that few companies actually get the most out of their brand portfolio as a whole and thus leave large sums of money on the table. This same research suggests that the explanation for the gap between realized and potential value is less to do with individual brand marketing and development capabilities, and much more to do with a lack of a systematic and well governed means for managing the portfolio of brands as whole. And although some of the root causes may differ, this observation holds true for almost all types of common organizational models: from decentralized country led mono-brand companies offering multiple products and services (e.g. LEGO, Diesel), to category led multi-brand companies (e.g. Unilever, Nestlé, Diageo) and even more general holding companies (e.g., LVMH, PPR).

As Alexis Nasard, Chief Commerce Officer of Heineken NV, states: “Brands are living organisms through which we touch the lives of our consumers. Our ability to deliver on their needs, hopes & aspirations through our brands – in sustainably distinctive and profitable fashion – is the primary driver of the long term success of this company”. Getting this right is worth a lot for companies. In the following commentary we argue that by applying four fundamental principles companies can unlock significant additional intrinsic future brand portfolios:

1. Ensure clear and continuous line of sight into brand portfolio performance & potential

2. Leverage truly distinctive consumer insights into winning portfolios with clear brand roles

3. Establish a governance model that reinforces clear accountabilities for managing the brand portfolio

4. Allocate resources across your portfolio of brands in as ‘strategic’ a manner as you would across your portfolio of businesses

* Brand Value Growth using Interbrand’s Valuation method

Diagnosing the Issue And Sizing the Prize

But first, consider the following questions:

1.Do you have multiple brands addressing very similar consumer needs and (needs-based) segments in key markets?

2.Do consumers appear confused and regularly switch between what they consider similar brands in your portfolio?

3. Do you have a large % of brands in your portfolio which are structurally losing share in their respective markets or categories?

4. Has the number of brands in your portfolio increased significantly in recent years without moving the needle in terms of overall (profitable) growth?

5. Do you have many brands in your portfolio which are losing money or marginally contributing?

6. Do your channel partners see several of your brands as directly competing with each other and therefore only placing part of your portfolio on their shelves?

7. Is your marketing spend too fragmented across brands and ineffective? Are your competitors outspending you in key categories or markets?

If you recognize any combination of the above issues, you are no doubt leaving money on the table in how you are managing your brand portfolio!

If it is so important, why is it so hard?

By examining the evidence we have gathered across a large sample of multi-branded companies (and a number of mono-branded companies with larger product portfolios), we come to similar conclusions with respect to what makes the task of effectively managing the brand portfolio so daunting. It appears to ultimately come down to three related drivers:

1. Pressure to deliver incremental growth

2. Leading to a significant increase in portfolio complexity

3. And a governance model that accentuates – rather than addresses – that complexity

As companies grow organically or through acquisitions and constantly diversify to satisfy ever-increasing consumer needs, they are constantly in search of ways to accelerate growth but in doing so expand their portfolios, adding complexity which is not always value-adding. More brands and product lines are added as opposed to taken out over time, portfolio cohesion becomes less clear and line of sight into performance is blurred. The fundamental relationship between certain brands and the consumer needs they aspire to serve weakens over time as companies continue to grow their portfolios. Brands often overlap and do not have clearly established roles.

In the meantime complex organizational models (multi-dimensional matrices often combining central marketing, categories, brand companies and country management) develop alongside the ever-increasing portfolio complexity, creating confusion and natural tensions with respect to where the actual accountabilities for managing brand portfolios lie. As a result few companies are ‘wired’ to implement a well-structured, top-down, and ‘zero based’ approach to resource allocation across brands. Most companies use a bottom-up approach, where the individual brands, categories and markets deliver annual budget requests which are “consolidated” at the center with minimal challenge and intervention (other than some high level guidelines).

Getting Line of Sight into Portfolio Performance

Delivering superior performance across brands is a challenging task, especially in an environment where companies have increasingly large and complex brand portfolios

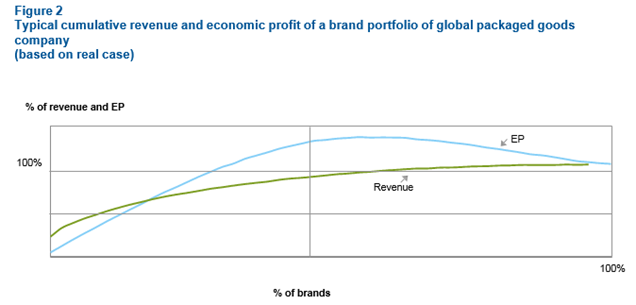

For example, the ten largest companies operating across the Beauty & Personal Care, Home Care, Apparel and Packaged good segments had, on average, 160 brands in 2010, with nearly 700 Country Brand Combinations (CBCs). The number of brands per company has been (and still is) only increasing further. As companies add more brands (and thereby multiple CBCs by main brand), portfolios become increasingly hard to manage. Revenue and profitability typically follow a Pareto distribution, as illustrated in Figure 2. A small minority of brands delivers the majority of the value and several brands are actually value-dilutive. In 2010, across those same ten companies mentioned above 10% of the brands delivered 75% of the revenues!

It would be tempting to suggest that pruning the portfolio is the immediate answer but although some brands may not be directly value-accretive, they can still play a significant strategic role in the portfolio. For example, Heineken has not seen a strong financial contribution in recent years from one of its important CBCs in France (33 Export). Nevertheless, through its aggressive positioning and promotional activities the brand plays an important strategic role in the overall portfolio of Heineken France by preventing competitors from entering a key segment. Given that brand value is a key driver of company performance and value creation , you would expect that most consumer companies would monitor and manage this closely. However, our research and experience suggest that many companies lack the ‘right’ line of sight into brand performance and positioning. These companies track several different financial and commercial metrics (e.g., relative price, relative share) but fail to join them up and integrate with the consumer- oriented metrics necessary to truly understand where the most profitable and accessible headroom for growth exists (headroom = total market minus your current share minus the share of competitors which is unlikely to switch). And in many cases getting proper line of sight is made more difficult by country or brand managers who use their own ways of measuring brand performance whilst not disseminating that information in a manner that allows for easy comparisons across the portfolio.

Most companies have a reasonable understanding of financial performance across the brand portfolio, with full P&Ls by Brand and by Country generated on a frequent basis. Few companies, however, are able to consistently generate full P&L information by Country Brand Combination. Brand equity is not properly presented in company balance sheets, although it provides a very important measure for investors. And perhaps most importantly, financial metrics for brands usually take time to be measured and by the time they are reported tend to be lagging indicators, reflecting past performance. Commercial metrics (current inidcators, e.g. Nielsen data on relative price and market share evolution in retail) therefore complement the financial metrics by offering a snapshot of current competitiveness, indicating relative performance vs. competition at any point in time.

Understanding historical financial and current commercial metrics are important in considering the relative strength of different brands in the portfolio, but are not sufficient to predict the future potential of a brand. Companies need a set of leading indicators that provide a sense of a brand’s evolution and future potential. It has to be both real-time and consumer based, whilst being closely linked to actual purchase behavior and/or prospective purchase intent. Although many companies invest millions in tracking consumer- based statistics like brand perception and brand awareness, few actually generate leading indicators that enable optimal decision making and specific actions. An example of a good leading indicator is new consumer recruitment, as any brand that fails to recruit new consumers will have very limited future potential. Other examples of leading indicators include the net promoter score (demonstrating how willing consumers are to recommend a certain brand), and data/insights related to switching behaviour (demonstrating from/ to which brands consumers are switching and why).

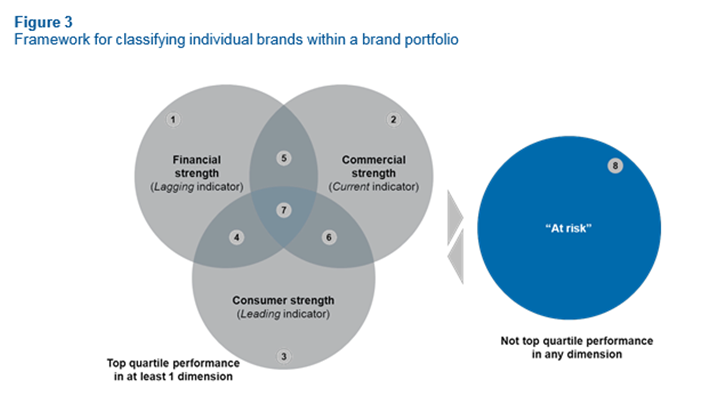

By combining simultaneous line of sight into all three indicators: financial (historical performance trends-lagging indicators), commercial (e.g. relative strength against competitors in retail- current indicators) and consumer (e.g. brand headroom on basis of consumer needs-leading indicators) companies will have the advantaged insights necessary to increase both the pace and standard of decision-making across their portfolio of brands. And by ensuring that the framework and core metrics are applied on a consistent and repeatable basis across each Country Brand Combination, companies can drive the most effective execution at the level where performance is managed and value is delivered.

Figure 3 below demonstrates one example of how this approach can be applied in practice. In this example the framework serves 3 specific objectives:

1.It provides a holistic view on the brand portfolio and gives insight in both the relative performance of brands, as well as the relative potential across brands

2. It helps characterize different types of brands across the portfolio that are in different stages of development and require different actions

3. It functions as a key input into resource allocation

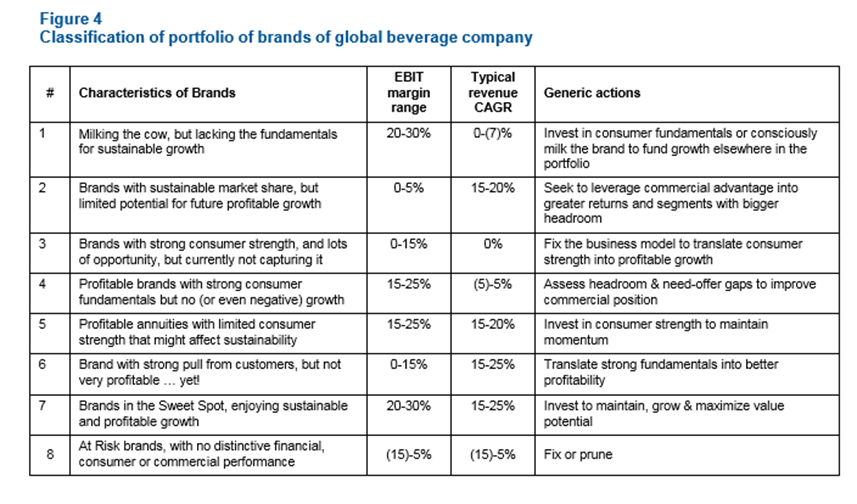

The three blue circles (financial strength, commercial strength and consumer strength) highlight any Country Brand Combination (CBC) that achieves top-quartile performance in the respective area. Some brands achieve top-quartile performance in one dimension (e.g. area 1), some in two dimensions (e.g. area 5) and some in three dimensions (area 7). For example, area 1 in Figure 3 includes brands that are achieving strong financial performance only, but have relatively weak commercial and consumer strength. These are typically big brands that are being milked, where consumer brand equity is decreasing and share is slowly eroding over time. Area 8 represents all brands that do not achieve not top- quartile performance in any dimension.

The power of this approach is that it helps distinguish different types of brands with a set of common characteristics, and therefore informs a set of tailored actions to be considered for delivering more value from not just each individual brand, but from the portfolio as a whole.

Figure 4 provides an illustration of how one company leveraged this framework to classify their brands into each of the eight different classifications. For each group of brands the company defined a specific set of actions believed to be aligned with maximizing the value of the portfolio as a whole. Though we believe the classification framework can be consistently applied across categories, the individual actions and targets (margin, growth, etc.) must be tailored by company and category.

Translating Distinctive Consumer Insights to Winning Brand Portfolios

Developing winning brand portfolios starts with better insight. And as described above, a central aspect of this insight is that it is related to a deep understanding of consumers, and what that implies for a brand’s positioning and true growth potential in any given market. Yet few consumer companies appear to make distinctive consumer insight a true source of competitive advantage. Many of the companies we spoke with admitted to have only “instinctive” views of what the real accessible headroom for their core brands is and where most of the headroom can be targeted (e.g. “we only have 2% market share in Russia, surely we should be able to capture 20%”). Others noted that their consumer insights are often confused with “consumer trends”, producing a high level view of evolving consumer needs but lacking a grounded perspective into what the brand represents as an overall consumer value proposition. And in many cases we observed situations where the amount of data on the consumer was overwhelming, but the company lacked a disciplined process and framework for translating those data into insight, insight into ideas and ideas into action. The president of one of the world’s largest retailers once said to us ‘I have enough consumer data to fill this conference room, but we don’t have a clear means of translating that data into profitable growth’.

Despite being a mono-branded company, LEGO is a good example of an erroneous association between consumer insight and its brand identity. Lego has been a huge success over the last 5 years with repeated double digit profit growth, outpacing all key competitors in an industry that is not growing overall. Before that however, they hit a rough patch which almost led to the demise of this great company.

Mads Nipper (LEGO CMO) described the situation: “Although we did a lot of consumer research, we still made a lot of mistakes with our consumers. One key consumer trend we observed was that young kids had less and less time available for playing. We subsequently thought that we could best serve our loyal customer base by essentially replacing our core offering with simpler and easier to put together LEGO models. Our customers reacted badly to this move and we lost significant share. Our core customer base now found our toys overly simplistic and boring (not LEGO worthy), and the segment we aimed at just wasn’t really into LEGO in the first place. We changed our portfolio too much, too quickly and moved away from our core brand values.”

Many companies produce and track lots of consumer data but what we often find is that they lack truly distinctive consumer insights, which we would characterize as follows:

- They are not the output of broad market research and panel data, but generated by highly focused and customized primary research

- They establish a deep understanding of the relationship between individual brands and the consumer

- They don’t just provide general information about consumer demographics, trends and attitudes, but real actionable facts around consumer needs, behaviors and economics

- They deliver insight into accessible headroom with clarity on the need-offer gaps that must be addressed to capture switchers

- They account for both ‘value of’ and ‘value to’ the consumer and thereby inform choices related to how to optimize price, offer attributes and marketing investment given consumer willingness to pay vs. cost to serve

- They don’t ignore the interplay between consumers and customers and therefore the role that different channels play in accessing demand

Getting from distinctive consumer insight to winning brand portfolios is fundamentally about leveraging insight into needs, behaviors and economics (and the linkages between them) to both position and invest behind brands in a manner that enables maximum capture of the accessible headroom for growth and profit pools over time.

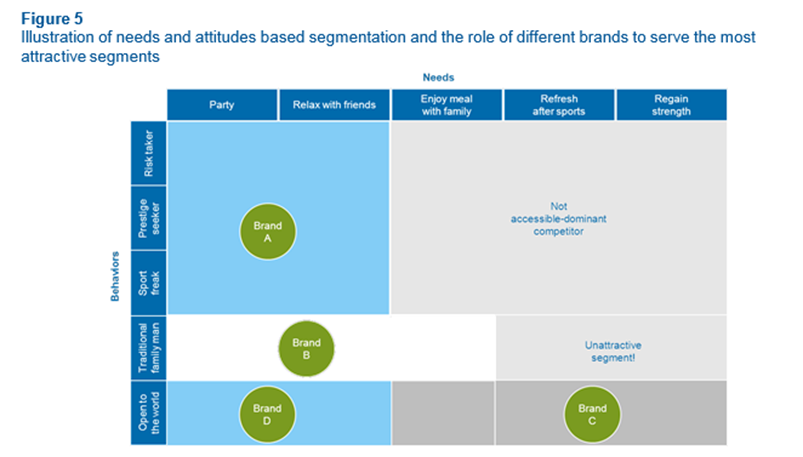

A better understanding of consumer needs allows for the definition of specific needs-based segments, on the basis of which different brand roles (and detailed strategies) can be defined within each market. A value- maximizing portfolio within a given market will cover the most important needs segments with non-overlapping and advantaged brands (see Figure 5). For each segment, we look at its relative size and expected growth, current and expected profitability, as well as its relative accessibility. It should be clear about what segments not to target – i.e., those that are inaccessible (e.g. due to a dominant competitor brand) or inherently unattractive (e.g., too small or with poor profitability and a strong presence of private label).

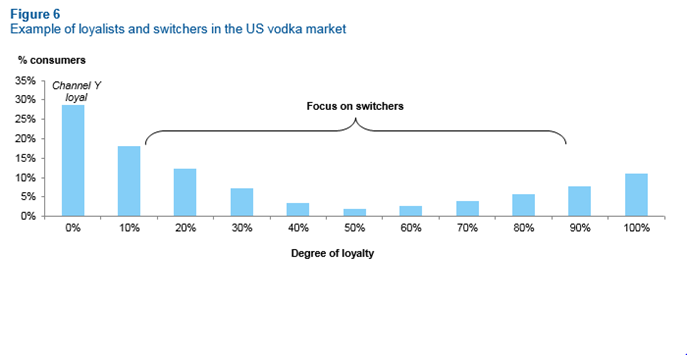

Better insight into consumer behaviors informs a clearer understanding of what current and future consumer demand represents truly accessible headroom for any given brand. Which consumers are fully loyal to your brand vs. being loyal to your competitors vs. those who regularly switch between different offerings in the market? What does this imply in terms of the demand that is most ‘up for grabs’, and potentially less expensive to acquire? Figure 6 illustrates how a major global spirits player leveraged insight into switching behavior as a basis for getting under the skin of where and with whom demand was likely to be most elastic, and therefore where a more targeted approach could most profitably increase their “share of throat’ within increasingly competitive US Vodka market.

Economics – and it’s linkage to consumer needs and behaviors – is the third part of the foundation for winning portfolio management. How do the economics of each brand into each consumer segment (and through each channel) differ? What does this imply in terms of where we can position our brands to go after ‘profitable switchers’? How does brand equity and value link to company value, and what does this imply in terms of the right tradeoffs for investment (whether through pricing, promotion, marketing, sales or innovation) both across and within the brand portfolio?

Insight into needs, behaviors, economics – and a framework for linking them together and leveraging them as part of the decision making process – is what we mean by translating distinctive consumer insights into winning portfolios. But none of this is feasible without an effective governance model that underpins it all.

Establishing effective brand portfolio governance

It is remarkable to see how many companies struggle with the challenge of establishing a governance model best fit for managing the increasing complexity of today’s brand portfolios. Companies that have been very successful growing 1-2 brands have often exceptionally creative people driving their individual success (e.g.

Prada) but those same people are often less well equipped to manage a portfolio. Portfolio companies (e.g. PPR) are very good in identifying brands in distress and taking a disciplined financial approach to building and managing the portfolio yet they sometimes delegate the management of the brand portfolio, with often sub-optimal results. And many large multi-brand companies struggle to translate excellence in their brand and category management processes into excellence in brand portfolio management. An ineffective brand portfolio governance model is typically at the core of each of these challenges.

When Alexis Nasard took over the role of Chief Commercial Officer at Heineken, he discovered to his astonishment that even the very successful Heineken ® brand had no central governance structure. There was limited central accountability (as well as no global P&L) for the brand which generated more than 20% of sales and an even higher percentage of Heineken’s overall profitability. At the same time “we were doing business with more than 1000 advertising agencies”. Despite continued growth in recent years, the brand had lost some of its edge and was losing share in key markets (e.g. USA, Netherlands). It no longer had consistency in terms of positioning (from super-premium in some markets to mainstream in others) and was not performing up to its potential. Alexis swiftly changed all this by taking a much tighter central control of the brand and establishing a mechanism (“brand reviews”) whereby core CBCs are now regularly under multi-functional review (whereby marketing, finance, strategy and operations and often even the CEO participate) to ensure clarity around targets, plans and accountabilities. Managing differently is starting to deliver big dividends with the Heineken ® brand rapidly regaining share in key markets.

Though each company’s portfolio, growth path and culture demand somewhat different organizational structures and processes, our experience and research would suggest a number of key principles should be adhered to in order to create the right governance model for any given brand portfolio:

- Best in class brand-management capabilities and clear accountabilities: Managing top brands requires a set of skills (strategic, creative, marketing science and financial) which in our experience is not something that many people have in combination within large organizations. It sounds obvious but given that top brands represent a core value driver for the company, they need to be managed by some of the company’s very best managers. Furthermore, it is important to be very specific about who is accountable for key branding decisions (e.g. positioning, architecture, promotion, budget etc.) and this cannot be a collective accountability. For example, there can be no compromise with respect to how you manage a global brand; it requires a fully centralized, top-down approach with respect to setting strategy, with local markets only responsible for adaptation to local trends and execution

- Distinguish between managing individual brands versus managing the overall brand portfolio: Brands are best managed in the context of the overall portfolio, even if a company mostly has local brands. The process (as an example) could be led by the CMO, in close collaboration with the CFO and sometimes the head of corporate strategy (the so-called Brand Portfolio Committee). This Committee would have regular discussions on overall portfolio strategy as well as performance of key brands and CBCs (structured around the eight different types of brands and key issues & opportunities that have arisen across

- Establish clear process standards and ground rules: The nature of the Brand Portfolio Committee discussions would be around things like managing performance issues, adding or removing brands from the portfolio, rolling-out key brands to new markets and changing resource allocation. There are several variants to how this may work in practice (e.g. brand company CEO could be a participant in this discussion), but the basic premise is to have a fact-based, continuous dialogue about how to maximize the value of the portfolio. While this sounds straightforward, there are few companies we have come across (e.g. Coke, Pernod Ricard) which actually do this well

- Place your top brands highly on the company agenda: The late Steve Jobs at Apple was saying that the brand can be seen in everything they do. While many companies view ‘brand’ as the domain of marketing, Apple understands that business strategy and the brand are indistinguishable. Brands need to be at the core of the top executive agenda and need to be managed as core company assets

One of the best companies we have found in managing brand portfolios is Pernod Ricard, which has significantly out-performed its main competitors in terms of both growth and profitability in recent years. As Thierry Billot (MD Brands) and Martin Riley (CMO) explained, Pernod Ricard has a governance model which may appear complex on paper but is extremely clear and focused on how brands are managed. Decentralization is the founding principle of the Group’s organization; companies work close to their markets, coordinated by the Holding Company defining the major strategic guidelines. Brand companies (with their own management teams) define global brand (portfolio) strategy and set-out specific guidelines on things like quality, positioning and communication. Market companies adapt global strategies to local market conditions and are responsible for local sales and distribution. In addition, the company has established clear performance objectives and roles for brands across the portfolio, as well as precise accountabilities. Furthermore, the “House of Brands” provides the overall strategic framework for the way key brands are managed (composed of Global Icons, Strategic Premium Spirit Brands, Strategic Prestige Spirits and Champagne Brands, Premium Wine Brands and finally Key Local Spirits Brands).

Putting Your Money Behind your Best Bets

Core brands require relentless attention and resources to keep them ahead of the pack. PepsiCo’s experience when it comes to brand resource allocation is a great case in point. After out-competing Coke in the mid-2000s with a strong focus on its core brands, the company began to under-perform in recent years despite a strong push to diversify into healthier products. Whilst expanding into these new areas, PepsiCo underinvested in its core brands (e.g. at the end of 2010 PepsiCo was investing only ~3.5% of sales on advertising versus ~8.5% for Coke), leading to a significant loss in market share. More recently the company has recognized the issue and has once again made it a top priority to focus investment behind its top brands.

As mentioned in our opening we see observe resource allocation to be one of the most significant challenges – and underdeveloped capabilities – as it relates to managing brand portfolios. The most fundamental issue appears to be the lack of a well-established strategic portfolio management capability at the center. The result is an inability for many companies to get resources and investment aligned with the highest value (i.e., ‘bang for the buck’) opportunities across the brand portfolio. Investment decisions are made on a bottom up and incremental ‘last year +/-‘ basis, with limited consideration of more substantive shifts.

Overcoming this challenge starts with the right governance model but also requires adherence to some fundamental best practice portfolio management principles:

- Only allocate funds to highest value opportunities (i.e., where the biggest and most profitable headroom is

- Prioritize resources for (and start with) the with most strategic brands in the portfolio

- Start by asking the question of how you can get more out of your current lead brands, before allocating capital to new things (e.g. M&A, new launches)

- Find the right balance between defending the core brands in the portfolio vs. playing offense to capitalize on new growth opportunities (be guided by intrinsic value)

- Don’t get into the habit of necessarily spending more to increase impact, there are always opportunities to allocate resources better across the portfolio to achieve the same desired impact

The Henkel Beauty & Personal Care is a good example of how CMO Tina Müller adheres to the above principles. The success of the Schwarzkopf brand since it was acquired by Henkel is truly remarkable (bought ~€500M of sales and turned it into an almost €~2BN business in a market which is only growing in single digits across the board) and it entails a number of very important lessons.

Ms. Müller introduced a new process for centralizing all marketing and innovation through a central innovation committee. The entire organization was asked to submit innovation ideas and the best ideas were selected to be reviewed in Düsseldorf. Roughly ~16% end up going to development. “This created a lot of excitement and a new dynamic around innovation. We now have a very disciplined process whereby we review new ideas on a bi-weekly basis, promote the best ones, get them into the market very rapidly for testing and retain only the ones that get real traction in the market place. Traditional market research does not work in our business; it is too slow, backward looking, biased and does not deliver a high return on investment. Resources are aligned “real time”

to where the opportunities for the brand are, as opposed to be allocated during budget reviews”. Key to the success of this concept is the ability of Tina’s team to measure real time how the different products and brands are performing in the marketplace at the right level of detail for each key financial, commercial and consumer indicator, so that they can understand accessible headroom and very quickly accordingly.

How to Make Progress

The above commentary has focused on our observations, research and findings related to the challenge of building winning brand portfolios. But how can companies make the most progress in strengthening their capabilities and realizing tangible value improvement?

Consider the following actions:

- Portfolio strategy and alignment: What is the governing performance objective for yourbrand portfolio (as part of the overall company strategy), what is the expected contribution and stated strategy for each brand, what performance is expected under current course and speed and what does this imply about the future shape of the portfolio?

- Portfolio performance, potential and ‘brand agenda’: Performance & potential: how would we classify the current portfolio in terms of the three key dimensions presented above: financial strength, commercial strength and consumer strength? What does this imply in terms of the highest value at stake issues and opportunities and the overall ‘size of the prize’?

- Organizational ‘audit’: How would we describe our current governance & decision making practices, how does this impact how we allocate resources and what has been the empirical linkage between spend and performance?

Establishing winning brand portfolios is hard, and there is no cookie-cutter solution that can be applied. But the linkage between winning brands and shareholder value creation is clear, and therefore putting this challenge front and center – and tackling it accordingly – is fundamental to any company’s future success. So stop leaving money on the table!