Introduction

Achieving sustainable and profitable organic growth requires more than new ideas, innovation, and strong execution. Rather, organic growth exemplars embed a set of institutional capabilities and a growth culture that define the organization and that are key enablers to realizing advantaged performance.

When the topic of superior organic growth arises, management teams often ask themselves “how can we be more like Apple, Amazon, or Google?” While there is clearly a lot to be learned from these companies, visionary product innovations like the iPhone or iPad or changing the paradigm for how the internet is used, as Amazon and Google have done, are not realistic goals for most companies.

In many ways, it is more revealing for companies to ask themselves what they can learn from companies like Nestlé and Costco. Nestlé, the world’s largest food and beverage company, has been able to achieve a 6% organic growth CAGR over the last five years, and has continuously increased its profitability each year, while competing primarily in low growth categories and markets. Similarly, Costco has achieved a 9% organic growth CAGR over the same time period (and 12% in the last three years), just below Whole Foods’s growth rate and ahead of Kroger’s and Wal-Mart’s. These companies are clearly doing something right to enable them to “beat the odds” in challenging businesses and markets.

This Commentary will explore what these companies and others like them have done to drive organic growth outperformance and offer ideas for what all companies can do to sustain an advantage in generating profitable organic growth.

Building Blocks of an Organic Growth Exemplar

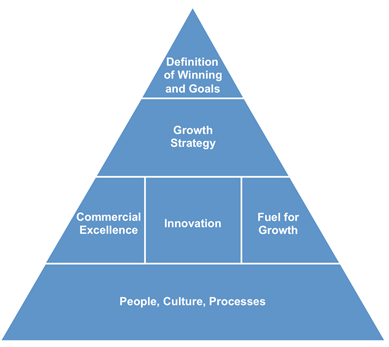

The common theme across organic growth exemplars is that they’ve put in place a set of organic growth building blocks that form the foundation for how they deliver and repeat strong organic growth performance. In essence, they’ve embedded growth capabilities deep into the organization. However, when the topic of an organization’s growth capabilities is discussed, the word ‘capabilities’ is often viewed as being synonymous with ‘people and processes.’ But this definition is too narrow. Embedding growth capabilities and a growth culture means infusing a growth orientation and growth disciplines into all aspects of how the business is run.

We see six building blocks as being fundamental to driving superior sustainable organic growth performance (see Exhibit 1). Organic growth exemplars may not be advantaged on each building block over time, but they have a clear point of view on each, which, taken together, helps define the company’s organic growth orientation and strategy and how it will be executed. These companies also have explicit processes in place for developing and refining their overall approach to organic growth, where and how they will seek to be advantaged versus peers, and how the whole set of building blocks will fit together in a cohesive way that can be easily understood, executed, and enhanced across the organization.

Now we’ll take a more in-depth look at each building block and what various exemplar companies have done to differentiate themselves in these areas.

Definition of Winning and Goals

Creating a growth culture begins with orienting the organization toward the right mindset – one that focuses on growth consistency and persistency. Being persistent starts with having explicit goals for consistent organic growth, over time, at both the company and business unit level. Jim Kilts, the former Chairman and CEO of Gillette, once remarked, “if you achieve just above median performance year-in and year-out, you will be number one over 5-10 years.” So, in reality, it is about being a step better most of the time vs. being much better some of the time. This definition of winning – consistent, persistent growth is relevant across industries, and is achievable even in mature, slow growing sectors. As an example, Nestlé defines winning based on this philosophy through its ‘Nestlé Model,’ which establishes objectives of real internal growth (RIG) of 5% each year as well as year-on-year profitability improvement, both of which it cascades to its various businesses. All business units should have an organic growth target – both short and long-term - and these goals should be grounded in each particular market and what it will take to achieve consistent ‘winning’ organic growth performance in them. In addition, these growth goals should be accompanied by complementary targets for growth in economic profit (i.e., net profit after a charge for the capital required to support the business and fund growth). Ultimately, it’s the combination of organic growth and economic profitability that correlates best to winning shareholder value performance over time.

Growth Strategy

Growth exemplars are highly discriminating in terms of where they place their ‘bets’ for driving organic growth. Given constrained resources (time, talent, and money), being clear about where a company chooses not to play is as important as being explicit about where it will play. In turn, ‘where to play’ should be described in market-focused terms, where the definition of ‘markets’ is broader than product categories and geographies: it not only includes these, but also factors in which brands, channels, customer segments (demographic and needs-based), specific customers, SKUs, etc. In other words, the company should specify where it will and will not participate at a highly granular level in order to enable strategic tailoring and flexibility. To help determine where it will play, top organic growth companies focus on where their real headroom is. Simply stated, real headroom is the market opportunity that the company doesn’t have less the market opportunity that the company is unlikely to get. ‘Unlikely to get’ segments of the market include consumers who are loyal to competitor brands, who purchase on a set of attributes that the company doesn’t deliver, and who have expressed a lack of intent, for whatever reason, to ever purchase the company’s products. Accessing headroom can be done through different means: stealing share in existing markets, growing existing markets, entering new markets, and / or increasing participation in higher growth markets. Most companies over-emphasize stealing share to capture headroom and drive growth, but exemplars actively pursue all four sources of growth and piece them together coherently under a common growth framework. However, the concept of real headroom can be extended beyond the segment lenses described above. For example, Wal-Mart uses real headroom to prioritize the relative importance of in-category, cross-sell, and new customer acquisition activities aimed at driving same store sales growth.

With an average of 100 million customers entering its stores weekly, Wal-Mart once assumed that delivering more same-store growth would require getting customers to ‘cross the aisle’ and buy in other product categories that they weren’t currently purchasing at Wal-Mart – for example, getting the grocery shopper to buy apparel. Better line of sight into switching behavior, share of wallet, and needs- offer gaps suggested that Wal-Mart still had significant real headroom with consumers within the category in which they were already shopping. In fact, better tailoring their offer to shoppers already shopping a category offered ~4x the real headroom when compared to driving additional cross-category purchases.

Quantifying real headroom requires having a deep understanding of consumer buying behavior, including loyalty and switching tendencies (and what drives these) as well as relative share of customer wallet. It also necessitates having insight on real and perceived sources of competitive advantage and where the company has a ‘license to win.’ Achieving this level of transparency is often

done through primary research that explicitly links consumer spend, buying behavior, drivers of this behavior, and their views of the strengths and weaknesses of each relevant brand. Most companies capture these inputs from discrete sources with no way of joining them up on a consumer-by-consumer basis. Being able to link these drivers together is critical to developing the complete picture that makes estimating and capturing real headroom possible.

Commercial Excellence

While most companies claim that they focus on the consumer, very few truly emphasize increasing consumer benefit – that is, delivering consumer value that the consumer is willing to pay for. Consumer benefit typically comes in the form of new product or service attributes or features – e.g., enhanced product, improved affordability, greater availability, increased convenience, differentiated loyalty programs, etc. Achieving true commercial excellence requires putting consumer benefit at the center of all decision making and execution. Those companies that consistently deliver consumer benefit are able to translate this into sustainable top line growth, not only through increased volume uptake, but also through increased willingness to pay, leading to improvements in both the top and bottom lines.

Whole Foods is distinctive in its strong focus on delivering consumer benefit. Walter Robb, Co-CEO, describes the company’s core values as follows: “The deepest core of Whole Foods, the heartbeat, if you will, is this mission, this stakeholder philosophy: customers first, then team members, balanced with what’s good for other stakeholders, such as shareholders, vendors, the community, and the environment.” This focus on the customer comes through in Whole Foods’s customer strategy: the consistently highest quality product; local tailoring of the product offer and store format; singular focus on pure and unmodified products; broad assortment of product categories and brands; and highly knowledgeable, passionate, and invested customer service. And consumers are willing to pay for what they view as superior product, product selection, and service: Whole Foods has generated gross profit margins of 8 pp higher than other largegrocery chains over the past five years (although the company is embarking on a plan to lower its prices in order to attract more customers and take share from competitors).

Being a commercial excellence exemplar requires understanding which product / service attributes most drive consumers’ purchasing behavior and which consumer segments are or are not willing to pay for them. This can be accomplished through standard consumer research or more sophisticated conjoint analysis, and involves looking at the business at a granular level (product categories, brands, demographic and needs-based consumer segments, etc.). Ultimately, companies that ‘master’ commercial excellence and the delivery of consumer benefit know better than their peers which consumer ‘needs’ to invest behind and which to ignore, enabling them to achieve advantaged rates of sales growth and profitability.

Innovation

Organic growth exemplars typically spend more on R&D as a percentage of sales than their peers, using higher rates of innovation to drive outperformance on growth. However, it’s not just the level of spend that makes organic growth exemplars unique, but rather, the way in which they invest to get the most out of their innovation dollars. Companies that are most successful in using innovation to drive growth open the aperture for discovery. Whether pursuing continuous innovation (i.e., the next generation of existing products or services) or discontinuous innovation (i.e., new or adjacent businesses), these companies look beyond their own teams and organizations for innovation ideas to diversify their sources of innovation. For example, they may simultaneously tap into internal R&D, have in-house venture investments, partner with peers, initiate business development relationships with other companies, engage in M&A, nurture relationships with academic institutions, etc. As a result of this, these companies are able to generate more and better ideas, while also reducing the overall risk of their investments.

As an example, P&G’s continuous innovation model is fueled by its partnerships with retailers, suppliers,and consumers (e.g., shopper studies that follow moms). It relies on these collaborators to help identify unmet consumer needs and gaps in the P&G offer that can be closed through product innovation. In contrast, Roche is an exemplar in discontinuous innovation (e.g., personalized healthcare, emerging technologies, breakthrough cancer drugs), but, like P&G, it wins by working collaboratively through its subsidiaries, Genentech and Chugai, as well as partnering with or investing in a number of biotech entities. These joint innovation projects are typically managed through a venture capital mindset: business cases and term sheets are developed with high standards and detailed performance tracking. While P&G’s and Roche’s approaches to innovation are divergent, they share a recognition that they will get further through collaboration and taking on multiple points of view – opening the aperture – than by ‘going it alone.’

Organic growth exemplars are also adept at managing the inherent tension that innovation creates between ‘growth today’ and ‘growth for tomorrow.’ They are able to manage this tension by:

- Making explicit decisions about the best balance between continuous and discontinuous innovation (and they tend to invest relatively more in the latter versus the typical company)

- Investing relatively more in total innovation than the typical company (as noted above)

- Using measures of performance that place enough emphasis on long-term performance (e.g., growth in intrinsic value) relative to current performance

- Ensuring that their management processes and organizational structures avoid inappropriate risk aversion and / or a built-in bias that stifles or kills value-creating innovations

- Implementing continuous ‘fuel for growth’ programs to help relieve the constant tension between growth and profitability that all companies face (elaborated to the right)

Fuel for Growth

Commercial excellence and innovation enable companies to better match their product / service offers with unmet consumer needs to drive growth. But these offer enhancements need to be funded, and growth exemplars typically excel at creating ‘fuel for growth’ by channeling ‘bad’ costs into ‘good’ growth opportunities. There are several fuel for growth mechanisms that growth exemplars use to enable themselves to deliver both growth and profitability simultaneously, more of the time. First and foremost, they instill a continuous productivity improvement mindset across the company. While this may seem at odds with also instilling a growth mindset, growth exemplars see continuous productivity improvement and continuous growth as two sides of the same coin. For example, Costco, Wal-Mart, and Nestlé, all growth exemplars, have also put in place six sigma- type programs. Second, growth exemplars apply the disciplines of commercial excellence to be highly discriminating in what features they add to and remove from their product and service offers by continually assessing what customers value enough to be willing to pay for (e.g., P&G, Whole Foods, Costco). Finally, growth exemplars employ the disciplines of agenda management – that is, focusing on activities and investments that will truly move the profitable growth needle, while minimizing activities and investments that either don’t demonstrate a strong linkage to growth or simply dilute the organization’s focus on growth (e.g.,Coca-Cola, Nordstrom).

People, Culture, Processes

The final piece of the organic growth puzzle concerns creating and reinforcing the values and enablers in the company’s culture and way of managing in order to embed growth into the company fabric. What does this mean in practice? First, it means making organic growth a top priority for both the c-suite and line managers, as opposed to one group to the exclusion of the other. Second, it means defining winning and setting goals across the company in a way that embodies consistency, persistence, and patience, which can only be done by adopting measures of performance that strike the right balance between the near-term and the long-term.

This starts at the ‘top of the house,’ with goals and incentives geared toward value creation over time, as opposed to over-emphasis on current EPS and bonus systems based on stock options. Third, embedding growth into the company fabric means transforming management processes into enablers instead of having them be impediments – i.e., starting with disciplines to assess real headroom, making the strategy development process consequential, and applying agenda management at all levels of the company. Fourth, it means incorporating the right language regarding growth, emphasizing terms like accessible headroom, consumer value, willingness-to-pay, and needs-offer gaps. Finally, embedding growth means developing a deep bench of growth-oriented talent, consisting of individuals in the c-suite and in line and staff positions who value and understand growth and what it takes to achieve it and who themselves aspire to be growth exemplars.

Summary

Delivering outperformance on organic growth is a tough standard, but it can be achieved by putting into place the organizational growth building blocks described above and by adhering to the themes that growth exemplars live by:

- Being a step better most of the time vs. much better some of the time

- Focusing on where the real headroom is

- Putting consumer benefit at the center of all decision making and execution

- Opening the aperture for discovery

- Channeling ‘bad’ costs into ‘good’ growth opportunities

- Embedding growth into the company fabric

Companies that turn these themes into action will not only become exemplars in organic growth, but will also position themselves to and invariably become better acquirers, better parents, and superior creators of shareholder value.