We recently attended a dinner with a dozen or so CEOs to talk about best practices in portfolio management. While we covered a wide range of topics, there appeared to be universal consensus that (1) there is widespread excess cash on corporate balance sheets that needs to find a productive home; (2) in a sluggish growth economy, investing to get additional organic growth is both difficult and won’t make a big dent in the cash balance; so (3) everyone is now looking for attractive acquisitions but the enterprise value-to-EBTIDA multiples (EV/EBITA) are so high that there are few, if any, good deals out there. Our view is a bit different on both organic growth (we believe there is far more opportunity in core businesses but that is a subject for another time) and whether the level of acquisition multiples is a real constraint.

Before addressing the question whether acquisition multiples are too high, we need to point out that the value of every acquisition, expressed either in dollars or a multiple, has two components: The first part is the “stand-alone value” (SAV) which, for a publicly traded company, is the value or market cap that prevailed before news of the potential deal leaked or was announced; for a private company, SAV is usually estimated using discounted cash flow analysis and comparable company multiples. The second part is the premium over SAV that was, or must be, paid for control.

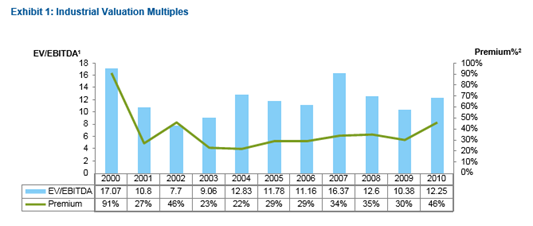

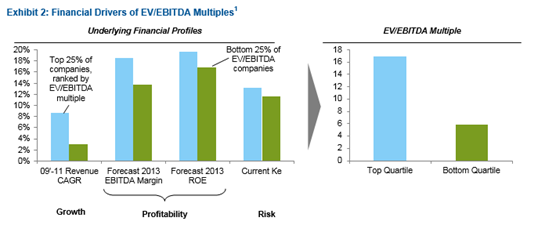

As can be seen in Exhibit 1, the multiple did increase in 2010 but was only slightly above the average since 2000 (the 2010 SAV multiple was 8.4 times and the premium paid around 45%). Both parts play an important role in deciding whether the valuation and multiple one must pay is too high. As we’ve described in previous Commentaries, theSAV reflects investor forecasts of profitability and growth over time plus investor assessment of risk as captured in the cost of capital. For mature companies with relatively stable profitability and growth near or below GDP levels, the key driver of SAV multiple is the sustainable level of profitability as typically measured by the return on equity (ROE). (The popular EBITDA margin is a key component of ROE.) For all other companies, the near-term levels of profitability and growth plus the assumed duration of above-average performance are the key drivers of the SAV multiple. So, whether the SAV is too high or too low depends on what one thinks about the forecasts over time and the risk assessment that are embedded in the multiple. For example, an average risk, mature company today earning an ROE of 12% should carry an EV/EBITDA multiple of around 7–8 times. If one believes the ROE and growth forecasts are too low and/or the risk assessment too high, the “warranted” multiple should be higher and the company will

appear undervalued. If one believes the forecasts are too high, the company will appear overvalued.

In Exhibit 2, we illustrate the specific forecasts that support low and high EV/EBITDA multiples on the left and show actual data for high and low multiples on the right. Note that the difference between top dampened a bit by a slightly higher risk assessment for the top quartile performers. Based on our experience over the years, the profitability, growth and risk assumptions underpinning most public company multiples tend to be quite reasonable. Occasionally we find companies where the market’s consensus forecast appear either way too high or too low based on our assessment, but making an accurate judgment of over and undervaluation is a very rare skill as evidenced by the small minority of professional money managers who consistently beat the market averages. Since it is unlikely that this skill will reside in the executive suite of acquisitive companies, acquisition strategy and target evaluation should depend almost entirely on the second valuation component: the premium that must be paid for control. Whether paying any sized premium is good or bad depends on the value of the combination benefits the transaction is likely to produce.

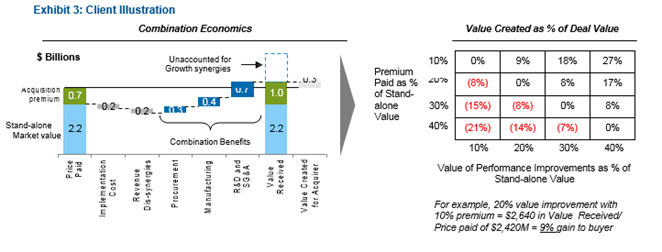

If the combination benefits are worth far in excess of the premium, the acquisition will create value for the acquirer; if they are worth significantly less, value will be destroyed when the deal closes. The combination benefits are worth far in excess of the premium, the acquisition will create value for the acquirer; if they are worth significantly less, value will be destroyed when the deal closes. The combination benefits come from two basic sources: Synergies and management improvements. Synergies are defined as an increase in cash flow or economic profit that comes from integrating the two companies. It is something that can only occur because of the transaction and has a favorable impact on one or more of the three value drivers: Profitability, growth and risk. Management improvements are actions that the buyer will take to boost profitability and/or growth or reduce risks that the seller could have taken but didn’t for some reason. An important consideration for determining the likely value of a combination benefit is one’s estimate of duration – how many years the benefits will last before they are competed away (a common analytic error is assuming that any combination benefit will last into perpetuity). Almost all of the attractive acquisitions we’ve worked on have a wide variety of combination benefits that come from many different sources. This point is illustrated in Exhibit 3 for an acquisition we recently helped evaluate.

1) Source: Thomson Reuters, Capital IQ and Marakon Analysis; Based on 200 largest publicly traded companies classified as industrial

In this transaction, the likely control premium was estimated at approximately 30% above market value based on comparable transactions or, in this case, $700M. This means that in order for the acquisition investment to create value for the acquirer, the present value of all combination benefits from the deal had to exceed $700M. However, in addition to the $700M control premium, we estimated that there could be as much as $400M of implementation costs and negative synergies, which put the hurdle for combination benefits at $1.1B. Fortunately, since the target’s business was closely related to the acquirer’s business, there was roughly $1.4B of “hard” cost synergies and management improvements that brought the mean expectation for value creation up to $300M. We then analyzed the potential for the softer revenue synergies and a more focused organic growth strategy, which we believed could create an additional $100M–$150M of value. Based on the analysis, our client formulated a four-part acquisition strategy: (1) pay no more than a 30% premium, (2) find ways to limit the costs and negative synergies to less than $400M, (3) capture all the hard combination benefits as fast as possible after closing, and (4) develop concrete plans to increase organic growth above the base case assumptions. If the strategy is executed well, the acquisition would generate $400M–$450M of net value creation for their shareholders.

As for answering the question in the title, note that if the company’s SAV is judged to be reasonable (not over- or undervalued by investors), this acquisition is expected to create value regardless of whether the pre-deal multiple was 5, 10 or 15 times EBITDA. As it happens, the pre-deal multiple was approximately 6.5 times, which expanded to approximately 8.0 with the control premium. However, if management had set an arbitrary cutoff of 7 times, the company would have missed out on a value-creating opportunity.

This way of thinking about acquisitions has three important implications for management:

1. First, management teams that limit their search for acquisitions to lower multiple companies will almost always acquire low profitability, low growth companies. While this strategy might make a lot of sense for acquirers that can wring value from these types of companies, it clearly limits the playing field and puts an unnecessary constraint on corporate strategy. So, unless there are clear core competencies within the executive suite that can significantly improve the performance of low multiple companies, a singular focus in this area is probably best left to private equity firms. Additionally, lower multiple companies rarely help boost the underlying growth potential of the company, whereas companies with higher growth and profitability often create a portfolio of future investment options that can accelerate the company’s core growth trajectory.

2. Second, acquisition strategy should focus primarily on a search for combination benefits. Management should begin with an objective assessment of the core competencies and strategic assets the company has both within the businesses and at the corporate center that can be leveraged to create combination benefits. The acquisition team should then conduct a screening process that is focused on finding target companies where the competencies and assets have the largest likely impact on profitability, growth and risk. Typically, the impact will be greatest for in- market transactions where the acquiring company is consolidating a market. The next largest impact will be found in adjacent markets – the closer the better. And the smallest impact will be found in new platform acquisitions where the initial deal is likely to be value neutral at best and can only be justified by follow-on deals (e.g., bolt-ons) that can create substantial value for the new platform.

3. Third, the analysis of potential acquisitions should also focus on combination benefits. They should be clearly identified and quantified in the evaluation stage. They should also determine the target and walkaway prices so that clear boundaries are set for the negotiating strategy. If an agreement is reached, confirming the size and likely duration of the various combination benefits should guide the due diligence process. And finally, if the deal closes, preserving the SAV while quickly capturing the value of the largest combination benefits should be the primary focus of the integration plan and activities.

Clearly, acquisition multiples do matter but they don’t determine whether a specific deal is likely to create or destroy value. That is the domain of premiums paid and the value of combination benefits, or “premium recapture potential.” Most successful acquirers combine creative strategies that find big combination benefits with a disciplined approach to evaluation, negotiation, due diligence and integration that convert the combination benefits into higher levels of profitability and growth, without an offsetting increase in risk.